BAROLO BOYS STORY

(vai alla Storia)

Barolo's and Barbaresca's - is oak ok now?

from Decanter.com

by Tom Maresca, 16 Feb. 2009 (link to original article)

In the late 1990s, Alba was infatuated with new French barriques. A decade on, TOM MARESCA looks at whether time has changed not

only these Barolos and Barbarescos, but also the mindset of producers.

I’ve never been persuaded by either the arguments for barriques or by the wines made with them. What I have loved, ever since I started drinking Barolo and Barbaresco 40 years ago, has been the wonderful character of Nebbiolo, and especially of mature wines from Nebbiolo.

As author Alan Tardi says in brilliantly describing the taste of a 30-year-old Barolo in his Romancing the Vine: ‘There are the wild, dark frutti di bosco flavours of blackcurrants and black cherries.

There are mushrooms, truffles – even a hint of manure – and, on the finish, the characteristic (though increasingly rare) qualities of leather and tar. This wine is not thick or jammy, the way so many today are made.

In fact, in the glass it appears almost transparent, garnet (not velvety red) with a touch of orange, not unlike the outer skin of an onion. It is subtle and refined – it doesn’t knock you in the head or get up in your face – yet it is incredibly intense.

It begins with the smell of violets and moist, rich, loamy soil; travels the full length of the palate from ripe fruit to tanned hide, and continues to evolve in the mouth even long after it’s been swallowed.’

In my experience, many of those wonderful characteristics of the Nebbiolo grape can be obscured, and in the most extreme cases totally blotted out, by the use of new barriques.

Because of their smaller size, barriques impose much more pervasive contact between the evolving young wine and the surface of the wood, thereby forcing greater extraction of sweet tannins from the oak into a wine that already has abundant tannins of its own.

With those sweet tannins, the wine also imports a distinct flavour of vanilla and, because of a combination of greater oxygen exchange encouraged by the porosity of the oak and other particles leached from it, the end result is a wine that has moved into a much darker colour spectrum and into a Pepsi flavour spectrum – characteristics which, until quite recently, have had enormous appeal in the international market, and so explain why so many winemakers pursued them.

Many people – producers, consumers, and wine critics alike – believed or hoped

that time would mellow those strong oak flavours and integrate them into a more traditionally maturing Barolo or Barbaresco. Well, it doesn’t and they don’t.

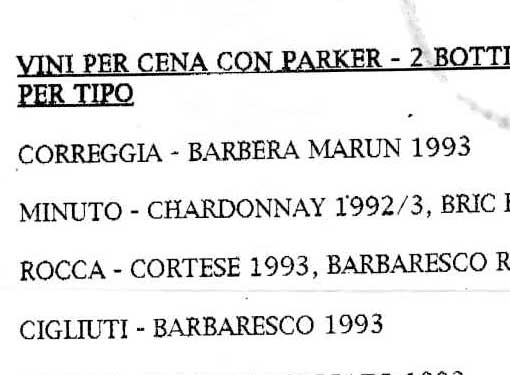

I’ve never been persuaded by either the arguments for barriques or by the wines made with them. Back in time Sunday morning at the Alba Wine Exhibition in May was devoted to a

journey back in time, to revisit the 1998 vintage. It was worth it.

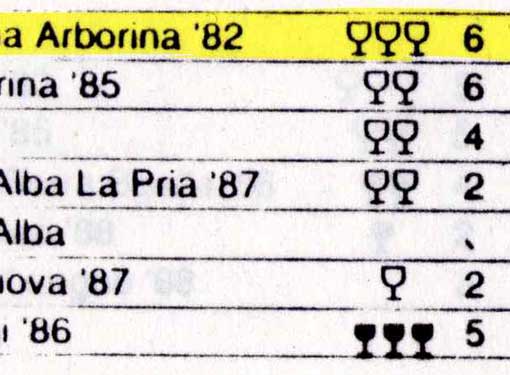

At 10 years old, 1998 Barolo and Barbaresco are showing clearly that they deserve the best of their original evaluations and far exceed the low estimates. The wines received mixed early reviews, largely because they followed the 1997 vintage that generated so much excitement in Italy, and were in turn followed by the magnificent ’99s.

In the wines of the Alba area, of which Barolo and Barbaresco are chief, ’97 is not holding up as well as the vintages that surround it. Both ’96 and ’98 are maturing in classic Nebbiolo style, as is 1999, deepening in flavours and complexity, seemingly picking up aesthetic and physical bulk as they age, behaving, as they often do, like the great red Burgundies to which they are justly compared.

Giovanni Minetti, general manager of Fontanafredda, describes those harvests: ‘1999 was the coolest of the more recent vintages. 1996 was the last very cold harvest we’ve had in the Langhe.

1997, on the other hand, was our first really hot vintage, and we weren’t ready for it: we were unsure how to handle the field work. By contrast, in ’96, the grapes were still green at the end of August. Septemberand October were perfect: they saved the crop, but we had to pick very late.

By those standards, 1998 was a much more normal, more average vintage for us.’ Pietro Ratti, proprietor of the Renato Ratti estate and president of the Union of Alban Wine Producers, takes a slightly longer perspective: ‘1998 wasn’t very lucky, because it came in the middle of the magic years – 1996, ’97, ’98, ’99, 2000, 2001.

It was one of the “less incredible” of those years, but certainly one of the most balanced of the six. If today I want to show what Barolo is to someone who doesn’t know Barolo well, I open a bottle of 1998.

I consider the vintage classic for its quality, its balance,and its typicity.’ My memory and old tasting notes tell me that this cluster of vintages probably marked the Alba area’s greatest infatuation with barriques.

In those days, barriques provided the flashpoint of the technologically driven culture wars between the partisans of new styles in winemaking and the defenders of traditional Barolo and Barbaresco.

The latter was customarily aged – and often had been fermented – in botti, large barrels, usually of Slavonian oak and often too old. The differences between these and the new-style wines aged in barriques (smaller barrels of usually new, usually French, oak) showed dramatically in the young wines.

Here, many newstyle wines were dominated by the vanilla sweetness of new oak or the espresso sweetness of heavily charred oak, as opposed to the more subdued, even reticent, leathery, black cherry fruit of young Nebbiolo as it showed or hinted at in traditionally made wines.

The barrique party at the time claimed that barriques gave Barolo and Barbaresco elegance – which was quite debatable – and that such wines appealed to the international market – which, alas, wasn’t.

Change in direction

This tasting of 10-year-old wines showed one thing conclusively: if you cellar Pepsi,

what you wind up with after 10 years is old Pepsi. The oak just doesn’t fade, unless it was moderately used in the first place.

Vanilla-flavoured wines remain vanillaflavoured, and espresso-flavoured wines still taste like strong coffee, with little evidence of the development of those dark flavours or complex subtlety of which Tardi writes.

The wines that in their youth had seemed less extreme – either completely traditionally vinified or only lightly exposed to barriques – now tasted much richer, more complex, worth

the waiting for: in short, much more as great Barolo and Barbaresco have always tasted – deep, dark and harmonious.

Fortunately, times change, and global fads change with them. The path Piedmont winemakers are now taking is clearly away from heavy dependence on

barriques.

Those small barrels have by no means disappeared, but are being used with much greater moderation than in the past. Perhaps it’s just a normal learning curve, as with any new technology (and barriques were certainly a new technology in Alba in the ’90s); perhaps it’s because, living in the regionwith the possibility of tasting young and old Barbaresco and Barolo all the time, the producers didn’t need to wait for a 10-year retrospective to discern what effect barriques were having on their wine.

According to the winemaker Federico Scarzello, ‘We’ve built a new concept of Barolo, so all the growers are going in the same direction. There are still many different styles, but the direction is the same: moderate wood, distinct Nebbiolo flavours, a wine full but not aggressive.’

Mariacristina Oddero is even more explicit: ‘There is a return to the use of large barrels, especially of Slavonian and Austrian oak. That oak is tighter and gives less oxidation; French oak passes too much air, accelerates the maturation too much.’

More than that has changed since 1998. Minetti of Fontanafredda explains: ‘The biggest changes we’ve made are in the fields, in the way we manage the vines and control our yields. The key things are to reduce vine vigour and grape quantity.

Perfect maturation of the tannins can be achieved by field management.’ If that is so – and evidence is mounting that, weather permitting, it is – then the winemakers of Alba will be able to achieve, without barriques, the soft tannins and elegant, youthfully accessible wines that they had turned to barriques to produce for them.

And if that is so, then we can hope for a 10-year retrospective in 2018 that will show no traces of Pepsi but taste only of glorious, mature Nebbiolo fruit.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Return of Traditional Barolos

By Ed McCarthy - from Winereviewonline.com

(link to original article)

I just returned from a trip to Piedmont, Italy, and I am happy to report that traditional Barolos are once again in fashion among the barolistas--the local name for Barolo winemakers. Roberto Conterno, proprietor-winemaker of the iconic Giacomo Conterno Winery, long the bastion of traditional Barolos, laughed when I brought up the topic to him. 'They never went away. I'm making Barolo the way I always did, the way my father (Giovanni Conterno) did, and the way my grandfather (Giacomo Conterno, the founder) did!'

It's definitely true that a dedicated core of winemakers such as Roberto Conterno kept the faith with traditional Barolo. But less than 30 years ago, in the early 1980s, a movement began among many younger winemakers in the Langhe (the area centering on the town of Alba that includes the Barolo, Barbaresco, and Roero wine regions) to change the way Barolo was being made. It had probably started with Angelo Gaja, the innovative wine producer in Barbaresco who has introduced so many changes in Piedmontese wines. Gaja was the first in the region to use French barriques to age his wines--first with Barbera, then with Barbaresco, and finally with Barolo.

Another innovator, the late Renato Ratti, introduced shorter maceration time for Barolo winemaking. Traditionally, barolistas would allow the juice to macerate (soak) with the grapeskins for 25 to 30 days. The Nebbiolo grape, the only variety used to make Barolo and Barbaresco, contains a huge amount of tannin and acidity. Ratti believed that Barolos made with such long maceration time picked up too much tannin from the skins and pips--making the wines too austere, and almost impossible to drink in the first ten years. At the Renato Ratti Winery in Annunciata (a hamlet of La Morra, a Barolo-zone wine town), Ratti introduced maceration periods of six to eight days for Barolo, an extraordinary change at the time. Ratti's goal of having his Barolos ready to drink within four or five years was achieved.

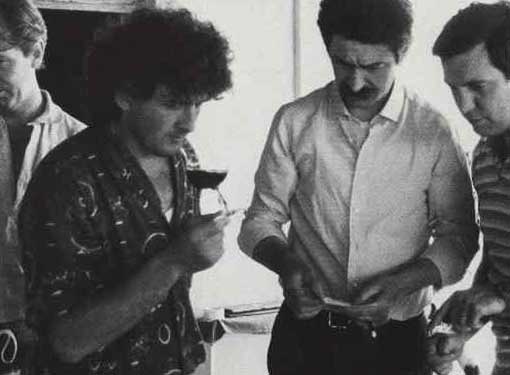

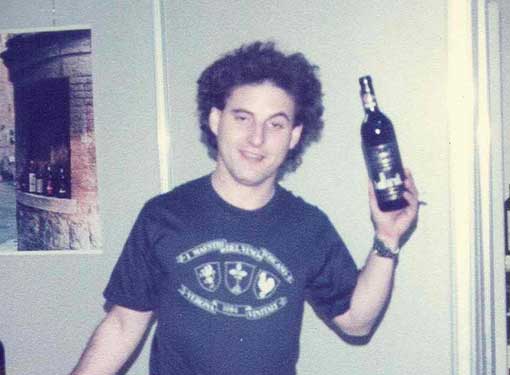

In the early 1980s, shortly after Ratti's innovations, a young group of Barolo winemakers, led by Elio Altare, Domenico Clerico, Luciano Sandrone, Renato Corino, and Enrico Scavino of Paolo Scavino Winery, banned together and declared that they were changing the (traditional) way in which Barolo was produced, claiming that the existing winemaking method made Barolos so tannic and unpalatable that they were often undrinkable for decades, and that some of these Barolos never 'came around.' In other words, the tannins outlived the fruit in the wines.

These 'young Turks,' as Elio Altare, perhaps the most vocal spokesman of the group, referred to themselves, shortened fermentation time to a week or less, aged the wines in wood for shorter periods, and in most cases used French barriques for at least part of the aging time. The resulting 'new-style' (the young Turks preferred 'modern') Barolos matured faster (usually within five or six years), were less tannic and less austere. In short, you could order a young, modern-styled Barolo in a restaurant and drink it without worrying about mouth-puckering tannins.

But the modern-style Barolos did not last nearly as long as traditional, full-bodied Barolos. I can remember drinking a 1982 (very good vintage) Altare Barolo in the early 1990s and it was dead in the water. I was shocked at the time. A few years later, I was drinking a 1985 (another good vintage) Sandrone Barolo along with a 1985 Vietti Rocche Barolo in a restaurant in Alba (Vietti was still a traditional Barolo wine producer, especially with its single-vineyard Rocche). The 1985 Sandrone was lifeless; the '85 Vietti Rocche was glorious!

What the young Turks had in common was the same agent/importer, an Italian-American living in Italy called Marco de Grazia (nicknamed 'disgrazia' by some traditional Barolo winemakers). Marco de Grazia and his younger brother Sebastiano believed fervently in the modern-style Barolo winemaking method, and I have heard that they encouraged all in their stable of Barolo and Barbaresco winemakers to change to the new method. Other Langhe winemakers who adopted the modern-style method (some of whom are represented by de Grazia) include Luigi Scavino of Azelia Winery, Chiara Boschis of E. Pira Winery, Silvio Grasso, Grimaldi, Giovanni Manzone, Paolo Manzone, Marco Marengo, Parusso, Seghesio, Conterno-Fantino, Rocche dei Manzoni, Roberto Voerzio, Gianni Voerzio, Gianfranco Alessandria, Mauro Veglio, Gigi Rosso, Icardi, and Luigi Einaudi in the Barolo region; and Albino Rocca, Bruno Rocca, Moccagatta, Rivetti, La Spinetta, and Sottimano in the Barbaresco zone.

Admittedly, modern-style Barolos and Barbarescos caught on with wine consumers, especially the younger generation. In the U.S., for example, barrique-aged Barolos--especially in ripe vintages such as 1990, 1997, and 2000--tasted a lot like the California Cabernets that American consumers were accustomed to drinking. From about the 1985 vintage on up to 2000, modern-style Barolos and Barbarescos and wines which combined aspects of modern and traditional style were more popular, at least in the U.S., than traditional Barolos--except for Barolo purists, such as yours truly and a handful of other eccentrics.

But then an amazing thing happened around the turn of the century. I like to think of it as American (and other) Barolo wine drinkers coming of age. More and more wine articles were written praising traditional Barolo. Traditionally-made Barolos and Barbarescos wines slowly caught on; one unfortunate aspect of this new-found popularity was that their prices rose. Ironically, during this period, two of the giants of traditional Barolo, Giovanni Conterno and Bartolo Mascarello, passed away. But their wines carry on with their progeny as winemakers.

Two signs of the changing winds in Barolo: Luciano Sandrone, never a total convert to modern-style Barolo, left Marco de Grazia a few years ago and is now being imported by Vintus Wines. Sandrone's Barolos are a blend of both styles; he has a short maceration (less than 10 days) but he does not age his Barolos in barriques. Perhaps even more significantly, de Grazia is now adding some traditional Barolo producers to his portfolio, notably Cavallotto and Luigi Pira.

Why do I love traditionally-made Barolos and Barbarescos so much? I love the pure, unadulterated (no new oak!) aromas and flavors of these Nebbiolo wines: ripe strawberries, tar, mint, eucalyptus, licorice, camphor, roses, spices, tobacco, and sometimes white truffles! Of course, you don't get all of these aromas in each wine, but you do get some of them. And these wines, aged in large, used Slavonian oak barrels which impart no oaky flavors, are incredibly more complex in flavor with age, taking on secondary aromas of saddle leather or forest floor. The fact that modern-styled Barolos don't age well bothers me a lot--in addition to the fact that they don't smell and taste the same as traditional Barolos and Barbarescos.

By the way, the assertion by some modernist Barolo producers that traditional Barolos are undrinkable for long periods of time and they finally dry up as the fruit dissipates might have been true with some traditional winemakers in the past, but not any more. All winemakers today know how to handle tannins much better (harsh tannins are really a thing of the past), and almost all wineries today are spotlessly clean, eliminating potential bacterial problems and other detrimental factors in winemaking.

The following is my listing of traditional Barolo producers whose wines I greatly admire: Giacomo Conterno, Giuseppe Mascarello (especially his Barolo Monprivato), Giuseppe Rinaldi, Bruno Giacosa, Bartolo Mascarello, Cavallotto, Cappellano, Francesco Rinaldi, Marcarini, Elvio Cogno, Poderi Colla, Brovia, Burlotto, and Luigi Pira. Other fine traditional Barolo producers include Giacomo Borgogno, Oddero, and Massolino.

Traditional Barbaresco producers that are tops include Bruno Giacosa, Marchesi di Gresy, Produttori del Barbaresco, and Castello di Neive.

Some very fine producers have incorporated what they consider the best of both styles in their Barolos and Barbarescos. They include Vietti (with winemaker Luca Currado lately bringing his winery closer to its traditional roots), Ceretto, Marchesi di Barolo, Pio Cesare, Aldo Conterno, Prunotto, Renato Ratti, and Michele Chiarlo.

I do think that some very good Barolos and Barbarescos are being made by the so-called modern producers. For example, I rank the Barolos of Roberto Voerzio among the best being produced today. And Gaja's wines, although very expensive, are always among the great Piedmontese wines every year.

Vintages to look for? Among the older vintages, 1988, 1989, and 1996 are all super, with the 1996 perhaps needing a little more time. Among the currently available vintages, 2001 and 2004 are great, with the 1999 and 1998 right behind them. Looking forward, both the 2006 and 2007 Barolos and Barbarescos should be excellent, when they finally arrive on our shores.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Jancis Robinson on oak barrels

Oakiness is now considered as 1980s as shoulder-pads, prompting an increasing proportion of winemakers to switch to larger casks

By Jancis Robinson - From "The Financial Times"

(link to original article)

Twenty years ago wine producers around the world measured their success by the number of new oak barrels they had in their cellars – preferably made from French oak, bought at vast expense from the world’s most experienced coopers (French ones) with the same capacity as those traditionally used in Bordeaux and Burgundy, 225 and 228 litres respectively – the size a strong man can turn on its side and roll along with relative ease.

An oaky taste, something a bit toasty and dense that overlaid the fruit, was fashionable for a while – especially in the Chardonnays and Cabernets that proliferated in virtually every wine region that could ripen them. There was also an exhibitionistic element in producers being able to show off just how much money they had invested in France’s well-conserved oak forests. (Today, a new barrel can cost €600.)

But fashions and tastes change. Now I find that for even the least sophisticated taster, “oaky” is a term of distaste, and even some of the most ambitious wines may be rejected by neophytes because there remains a trace of the oak barrel in which they were kept in their youth to give them the potential to age – although the wines are designed to be drunk long after any perceptible trace of oak has been subsumed.

Skilled winemakers are keen to put suitable wines into oak for a year or two before bottling to expose them to the very slow oxidation that helps clarify and stabilise them without more brutal chemical or physical alternatives. Oak also encourages a sort of complex marriage-brokering between the wines’ many constituent parts. Wines tend to come out of barrels more complex than when they went into them.

Partly in response to the change in consumer tastes, an increasing proportion of winemakers are eschewing the traditional small barrel size, often called a barrique, for bigger barrels in which the proportion of wine in direct contact with wood is reduced. This is particularly marked in places such as Italy’s top wine regions Piemonte and Tuscany where, before the advent of the barrique and a widespread but temporary belief that it would somehow confer French magic on their wines, large old oak casks were the norm.

The late Luigi Veronelli, an influential Italian wine writer, was so enthused on a trip to California in the 1980s by what barriques did to wine that he convinced many of Italy’s top wine producers of their virtues. This led to a wave of concentrated, oaky Italian reds and whites, but there is now a distinct return to larger oak casks. On a recent short visit to Tuscany I was given samples of the same wine based on the local Sangiovese grapes aged in different sizes of oak and it was notable how much more refined and precise the wine aged in 500-litre casks was – refinement and precision being 21st-century virtues. Think of oakiness as shoulder-pads.

But larger casks are also invading the classic French wine regions which have traditionally only used the classic smaller barrels. In Burgundy last week Grégory Patriat, perhaps most lavishly funded young winemaker in Burgundy in his capacity as négociant for [Name Name to come], Jean-Claude Boisset’s “viticulteur-winemaker”, could hardly contain his enthusiasm for what 500-litre barrels do for his fine white wines. “They give more purity, more tension, make the wine more crystalline, give it more minerality.” (Minerality is a very early 21st-century virtue.)

He doesn’t use 500-litre barrels for his reds, arguing that they don’t soften tannins as effectively as the Burgundian 228-litre pièce, but, he says, “since 2007 we have rediscovered our whites thanks to 500-litre barrels – and they’re cheaper!” The larger barrels may be more difficult to handle, but they take up much less space per volume of wine than traditional smaller casks, provided of course that your cellar is not so cramped that you cannot even get a larger size through the door (a consideration in many small, family-owned caves in Burgundy).

The celebrated French wine-writer Jacques Dupont overheard this conversation and volunteered that in the Champagne region, to which he was returning that night, a similar phenomenon is already evident. Oak ageing of the base wines for champagne has been increasingly fashionable, but many producers wishing to reduce obvious oakiness are introducing larger casks, and – a significant qualitative and economic factor – reusing them more often.

Again in the shoulder-pads era, the percentage of new barrels used – preferably 100 per cent – was considered a measure of quality. Today, it is no longer regarded as shameful – at the pre-eminent Bolgheri winery Sassicaia it is positively relished – to admit to reusing a certain proportion of barrels once, or even twice. Used barrels tend to move down the ranks. In Bordeaux, for example, a barrel used for first-growth Château Lafite in its first year may be used for the second wine Carruades de Lafite in its second year and then shipped down to their property in the Languedoc Château d’Aussières for its third and fourth years.

Less obvious oakiness is by no means restricted to Europe. Australia has long had a tradition of using 300-litre “hogsheads” and larger “puncheons” to mature its full-throttle reds, and reduced oak flavour has played a major part in perhaps the biggest and fastest stylistic turnround the wine world has ever seen, Australian Chardonnay’s recent rapid weight loss. Even in California, where oak tolerance can seem endemic, barrel salesman Mel Knox, who sells the hugely reputable Taransaud and François Frères barrels to some of the least cash-strapped wine producers in the world, reports that he sold 200 500-litre barrels last year and perhaps 10 of the 600-litre demi-muids commonly used in the Rhône valley.

A lower cooperage bill seems in tune with current austerity, but the tonneliers are not doing too badly. The latest toys for trendy winemakers are an array of fine wooden fermentation vats to be used, just once a year, before the wine goes into whichever barrels are chosen for it.

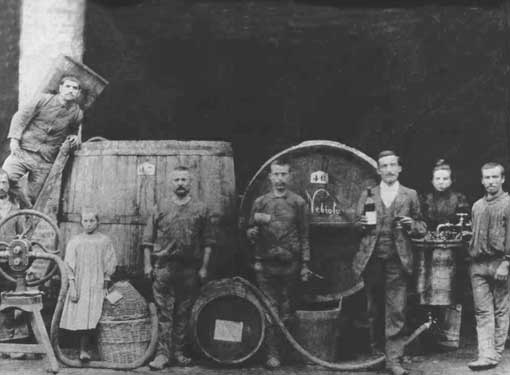

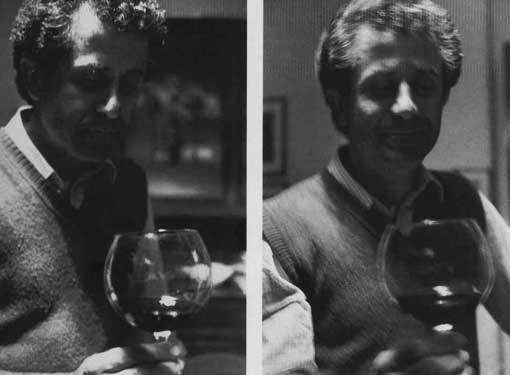

(photo credits: Elio Altare, Chiara Boschis, Giovanni Manzone, Marc de Grazia)

BUY YOUR COPY AT THE LOWEST PRICE OF THE WEB

(Clicca qui per ordinare il film dall'Italia)

How to order Barolo Boys from Outside o Italy? No problems at all, just choose your option and place your order.Watch it in HD streaming (1), buy your DVD copy (2), the exclusive Winelover Edition including a DVD of extra contents and the film Langhe Doc (3),

or the Sommelier Edition adding our new wine movie Wine Roads (4).

Paypal and any type of credit cards are accepted. We will send you an email to confirm shipment address.

All dvds are fully english subtitled and we will send you NTSC or PAL dvd according to your country of origin. Worldwide shipment.

For other options (multiple DVDs, payment through bank transfer..) please write to info@produzionifuorifuoco.it

Film Streaming

from $3,49

- 64 minutes

- HD QUALITY

- 48hrs access or download

- SUBS: ENGLISH/SPANISH

- CROATIAN/CATALAN/JAPANESE

DVD

€15,9

- 1 DVD

- 64'/

- English subtitles

- Shipment Included

- Worldwide shipment

WINELOVER EDITION. 3 DVD

€34,9

- Barolo Boys DVD

- Extra Contents DVD

- Langhe Doc DVD

- Shipment Included

- Worldwide shipment

SOMMELIER EDITION 4 DVD

€39,9

- Barolo Boys DVD

- Extra Contents DVD

- Langhe Doc DVD

- Wine Roads DVD

- Worldwide shipment